|

|

|

Mark Le Fanu and Sally Laird

The Tarkovsky Family Background

Mark Le Fanu is a Danish-based writer and film historian who 20 years ago wrote the first ever book-length

study of Tarkovsky in English, The Cinema of Andrei Tarkovsky (BFI Books, 1987). Sally Laird is a writer and translator from the Russian.

This article has never before been published and is presented here with the kind permission of the authors. Copyright 2008 Mark Le Fanu & Sally Laird.

Mark Le Fanu writes:

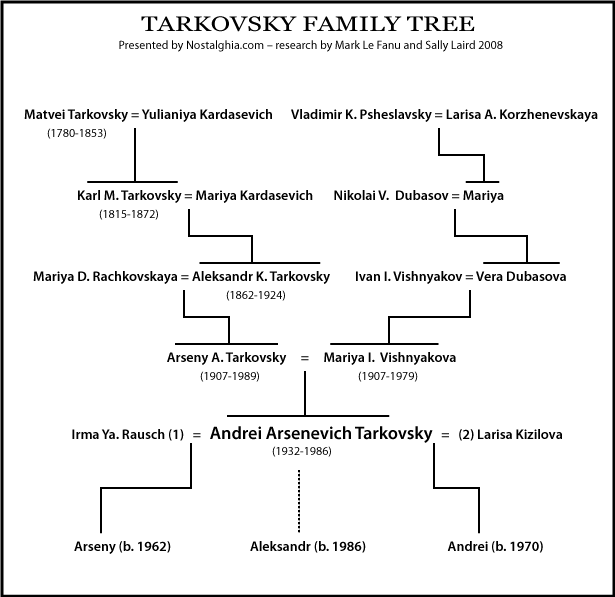

"The new book on Tarkovsky that is coming out this month (Tarkovsky, edited by Nathan Dunne, Black Dog Publishing) has a section containing poems by Andrei’s father Arseny, illustrated by rare captioned photographs of the family taken from Marina Tarkovskaya’s archive. (Marina is Tarkovsky’s younger sister.) The book in which the images first appeared, Marina’s beautiful memoir Oskolki Zerkala (Shards of a Mirror, Moscow, 1999 — as yet untranslated into English) contains a wealth of materials from which it is theoretically possible to put together a fairly detailed family tree on both Andrei’s father’s and his mother’s side. Since, however, Marina’s book doesn’t do this explicitly, I thought it might be interesting to readers of nostalghia.com to construct such a family tree myself.

My wife Sally Laird, a translator from Russian, helped me to compile the information on Tarkovsky's family tree from Marina's book and composed the captions to the photos. Our friendly webmaster Trond Trondsen has cleverly adjusted and designed the family tree for these pages. Here it is. Dates only on Andrei's father's side I am afraid."

This is a simplified version (direct line only; no siblings shown). Click graphic for more detail.

COMMENTARY AND INTERPRETATION

(a) The father's line

The Tarkovsky branch of Andrei’s ancestry was originally Polish and Roman Catholic, settled for generations in the Ukraine. Contrary to what has sometimes been written, there is no Tarkovsky connection with Daghestan or the Caucusus – no “princely forbears”. The most remote family member of whom there is clear knowledge, Woyzcek Tarkovsky, moved from Lublin, in Poland, to Zaslav (today Izyiaslav) in the Wolyna district of the Khmelnytsky province of Polish-ruled Western Ukraine at the beginning of the 18th century. It is recorded that he and his son Frantz owned the villages of Orlinets and Bylinets: gentry figures therefore or (what amounts to the same) minor nobility. The titre de noblesse and privileges attached to this condition are contained in a document in Marina’s possession, written in Polish in 1803, confirming in passing that the family was still Roman Catholic. (Incidentally, the Tarkovskys were never serf-owners.)

The Tarkovsky line becomes continuous from the time of Woyzcek’s descendant Matvei (1780-1853), who also lived in Zaslav, married a certain Yulianiya Kardasevich and fathered three sons of whom the middle one, Karl (born 1815), was Andrei Tarkovsky’s great grandfather. By this time, as a result of the various partitions of Poland, the Ukraine had been assimilated into Russian sovereignty. Following family traditions Karl enrolled in the military as a boy, transferring at the age of 17 to the Cadets before retiring in 1850 with the rank of Captain of Cavalry. In his post-military life he became a pillar of the local dramatic society. He too, like his father, married a Kardasevich, Mariya Kaetanovna, and brought up four children. At some stage during his lifetime the family converted to Orthodoxy, becoming, in effect, Russians by doing so.

As just remarked, the family of this couple comprised four children, three girls and a boy. The boy, Aleksandr Karlovich Tarkovsky, Andrei Tarkovsky’s grandfather, was nine years younger than his closest sister, Vera. When he was ten years old both his parents died of cholera, so orphaned Aleksandr was transferred to the guardianship of another sister, even older, Nadezhda, together with her husband I. K. Tobilevich who took him eastwards to live with them in the town of Elisavetgrad (now Kirovohrad), at that time a steppe settlement, small but cosmopolitan, containing a mixture of Ukrainians, Russians, Poles, Jews, Germans and Serbs. Tobilevich, Aleksandr’s guardian, appears to have been an interesting character. He occupied the post of Secretary to the Police Commission, and was thus a pillar of society; but like his father-in-law Karl Matvievich Tarkovsky he was also an actor and, under the pen-name Karpenko-Karym, a dramatist who wrote plays sympathetic towards Ukrainian independence.

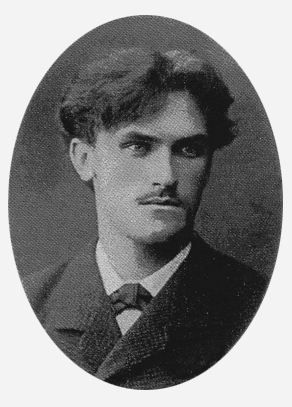

Following the abolition of serfdom in 1861 and the stormy decade that followed this (the decade of revolt recorded by Turgenev in his classic novel Fathers and Sons), social protest was much in the air. The technical school in Elisavetgrad to which Aleksandr was sent had a gifted headmaster, Zavadsky, who encouraged debate about issues of the day – issues that included, of course, the morality of terrorist action. Newspapers of the various social factions – Land and Freedom, People’s Will, Black Re-distribution – circulated clandestinely. At this school, and subsequently in student circles at the universities of Kiev, Petersburg and Kharkov where he went on to study in the early 1880s, Aleksandr imbibed the spirit of the times. A strikingly handsome figure as one can see from the photograph below, he is described by a contemporary as “honest, proud and thirsty for justice”: a dangerous burden to bear in autocratic Russia. Personal nemesis descended in 1884 when he was arraigned by the court in Odessa for “organizing public readings in preparation for revolutionary activity” – a just and accurate accusation as it happens, since Aleksandr at the time was “librarian” of the local cell of the most ultra of contemporary terrorist factions, the Narodnaya Volya (People’s Will). (It was this organisation that, three years previously, in March 1881, assassinated Tsar Aleksandr II.)

Exile followed to Irkutsk in Siberia for a period of five years (1887-1892). During this time Aleksandr appears to have undergone a change of heart. A nineteen and a half page letter written in French to Victor Hugo (but never sent) exists in the Ukraine State archive; in it he begs the famous poet to intercede on his behalf, promising that he poses no threat to the established social order. It would be interesting to know more about Aleksandr’s inner turmoil at such a crucial crisis in his life and social thought (the letter itself, printed in Marina’s memoir, records his intense suffering in solitary confinement, faced with the prospect of exile, and begs for help in heart-rending terms, but it says little about the morality – or immorality – of terrorist action). What is known is that on release he returned to Elisavetgrad and found employment, under Tsarist surveillance, as secretary to the head of the local zemstvo. Subsequently he was assistant accountant, and then accountant, at the City Public Bank, never rising above these relatively minor posts because of his chequered past. (Meanwhile, however, he did continue to write poems, articles and short stories.)

Aleksandr Karlovich Tarkovsky (1862-1924), Andrei and Marina’s paternal grandfather, at the age of 18, four years before his arrest for revolutionary activities. His life was marked by loss: first of his sister Evgeniya, then both his parents (they died on the same day of cholera when he was ten); then his sister Nadezhda, who had taken his mother’s place. His first wife Aleksandra, who had waited patiently for him throughout his exile, lived only five years after their marriage; his son Valery died aged 19 in battle during the Civil War.

Andrei first saw this photograph in 1948, when he was sixteen. Marina writes: "There was something mysterious and romantic in [Aleksandr Karlovich’s] appearance that captivated Andrei. He even started knitting his brows more often and kept looking at himself in the mirror to see if he had acquired the same vertical line that grandfather had. When you get to know Aleksandr Karlovich better…it becomes obvious that Andrei inherited many of his features. From an early age certain family characteristics made both grandfather and grandson incapable of fitting in with the circumstances they lived in — whether in the epoch of the early 1880s, or the years of 'socialist reconstruction'. From early youth [both men] were... restless and searching."

Aleksandr Karlovich Tarkovsky married twice: his first wife was Aleksandra Andreevna Sorokina, the fiancée who supported him in exile; the second (after Aleksandra’s death) was Mariya Danilovna Rachkovskaya, daughter of a Kishinev postmaster and court counselor. On her mother’s side she was descended from Romanians and it is she, apparently, who brought dark hair into a family which up till then had been primarily light-haired and blue-eyed. Mariya Danilovna, in turn, became the mother of two boys, Valery (1904-1919), who died young in battle, and the poet Arseny (1907-1989), the film-maker’s father.

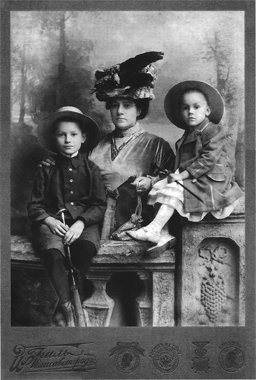

Mariya Danilovna Tarkovskaya (1867-1944), Andrei and Marina’s paternal grandmother, with her sons Valery (left) and Arseny (right) in Elisavetgrad, 1911. Mariya, née Rachkovskaya, was the daughter of a Kishinev postmaster and court counselor. She was an independent woman of 35 and had been working as a teacher for eleven years when Aleksandr Karlovich Tarkovsky began assiduously courting her. He was then a lonely widower, his first wife having died in 1897. The courtship – conducted mainly through the medium of letters – was prolonged; Mariya Danilovna did not at first return his feelings, and kept prevaricating. She finally gave in after Aleksandr carried out his threat to lie on the floor of the church at a friend’s wedding, shouting and stamping his feet until Mariya agreed to marry him.

Valery (“Valya”), Arseny’s brother, on the left, was a gifted boy with a passion for aviation and astronomy who was swept up at the age of fourteen by enthusiasm for the revolution, joining the SRs and becoming one of the organisers of a band of revolutionary anarchists. It was in vain that his father, whose life and career had been destroyed by politics, attempted to cool Valya’s revolutionary ardour; to his parents’ grief he ran away from home to fight alongside the Reds and was killed in battle in May 1919. For many years the Tarkovskys kept two shells from the Black Sea on which were inscribed the brothers’ names. When Andrei was born, Arseny commented that he resembled his (Andrei’s) long-dead uncle — apparently they shared the same green eyes. Click image for larger version.

Arseny Aleksandrovich Tarkovsky (1907-1989), Andrei and Marina’s father, pictured here in 1942. One of the great Russian poets of the 20th century, he had to wait until his mid-fifties to publish his first collection (Before the Snow, 1962). Eight other volumes followed. For most of his lifetime he was best known as a gifted translator, and during the war worked as a correspondent and composer of verse for the army newspaper Battle Alarm. Arseny was thrice married: in 1937 (when Andrei was five, Marina two) he left his first wife, Mariya Vishnyakova, to join Antonina Aleksandrovna Bokhanova; ten years later he left Bokhanova for Tatyana Aleksandovna Ozerskaya, with whom he spent the rest of his life. In 1940 he became a close friend of Marina Tsetaeva, whom he had long admired; Marina, his daughter, was named after her.

(b) The mother's line

Andrei’s mother’s side of the family is equally interesting. There is perhaps no need to remind readers that it’s the mother, Mariya Vishnyakova, and not Andrei’s often-absent poet father, who is the focus of Tarkovsky’s great autobiographical film The Mirror. She too, through her own mother’s line, was descended from Polish nobility. An early Victorian photograph exists of her great grandfather, Vladimir Ksaverevich Psheslavsky, seated at a table with his wife Larisa and Larisa’s brother. Frock-coated and cane in hand, with his trim goatee beard and direct confident gaze, he looks every inch the minor aristocrat. At some time in the 19th century, the Psheslavskys sold their estate to Tolstoy and moved to Moscow. Vladimir had four beautiful daughters, one of whom, Mariya’s grandmother (also called Mariya), married a certain Nikolai Vasilevich Dubasov who after a career in the army moved into the expanding railway business, playing a major part in the construction of the Moscow-Kiev line. Strongly “Russian” in looks, with high Slavic cheekbones and a shock of thick hair, he was admired by friends and acquaintances as a kind but strict patriarch. (Whether through jealousy, or just puritanism, he wouldn’t allow his strikingly attractive wife’s portrait to be painted.)

This couple had four children, three girls and a boy. The boy, handsome Vladimir Nikolaevich (“Volodya”) - the black sheep of the family – caused his family great sorrow by running off with a maid to Odessa for three years. When he finally re-appeared – by that time married to another woman and a father of two - he horrified the servants by showing himself tattooed from head to foot with a giant snake whose forked tongue emerged from his collar and curled around the back of his neck. Soon after his reappearance, he died of drink. His daughter Natalya married a Kiev landowner at the age of 17, while his son Georgy disappeared without trace in the Civil War.

Meanwhile, Voldya’s three sisters (Andrei’s grandmother and great aunts) were each strong and interesting personalities. Nadezhda, who married a doctor, V.I Guryanov, had a career as one of the first women doctors in Russia. Lyudmila, who died aged 99, married a royalist general named Alexei Ivanov in the Rostov Grenadiers who (unlike most of his regiment) survived the Civil War, only to die of typhus in 1924. The third sister, Vera Nikolaevna, Andrei and Marina’s grandmother, was apparently a captivating personality. Marina describes her as “not a beauty; but she was cheerful, coquettish, sang well, and loved to dress up. She had wonderful chestnut hair and lively, oriental-looking brown eyes”. This Vera married twice: firstly a judge, Ivan Ivanovich Vishnyakov, by whom she bore two children, including Mariya, the film-maker’s mother; next, when this marriage failed, a kind and impressively humane doctor, Nikolai Matveevich Petrov (1866-1936), an acquaintance of the Pasternak family and later a friend of the poet. It was in Nikolai Matveevich’s family house in Zavrazhe, on the north bank of the Volga, 360 km north east of Moscow, that Andrei Tarkovsky was born, on 4th April 1932.

Conclusion

To be modestly proud of one’s family background seems to be a universal trait of human nature. “Where does my family come from?” is part of one’s deepest identity. Thus one of the most egregious (and indeed wicked) aspects of communism was its categorical downgrading of family relations — especially if the family concerned had shown any distinction in pre-revolutionary times. To be descended from, or connected to, the wrong class grouping could and often did have fatal consequences. Fortunately, the hand of the state — even so monolithic and fanatically focused a state as the Soviet Union in the heyday of bolshevism and Stalinism — was unable to pry into every single family drawer (though no doubt it would have liked to). Albums and photographs circulated quietly, letters and papers were passed down from generation to generation, family anecdotes re-told with new embroideries. The social knowledge contained in these transactions could not be confiscated or eradicated. The family tree of the Tarkovskys outlined above provides in this context a footnote to the moment of history opened up by the release of The Mirror in 1974. There for the very first time ever in the Soviet Union a private family history — that of the film’s director, Andrei Tarkovsky — was illuminated, in public, without permission from, or apology to, the authorities.

In the age of the internet of course we take such rights for granted, but it was not always so; far from it. Family trees in communist times tended to be closely guarded secrets. Maybe it is not much of a claim, but we make it anyway: it is good that this is no longer the case.

|

|

|